THE SUSPICIONS Of MR ASHWORTH

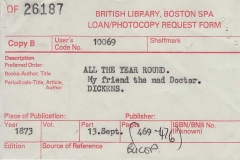

“All the Year Round”, published 13th September 1873 (Conducted by Charles Dickens.) From page 469 Dickens details a visit to the Asylum giving clues to it being Wakefield and describes in great detail people and events.

Lawrence Ashworth the curator of the Stanley Royd Museum decided to fully investigate the validity of the text in relation to Charles Dickens dropping in for a glass of sherry with Dr Crichton-Browne.

MY FRIEND THE MAD-DOCTOR.

Lawrence says….

Some mystery surrounds the authenticity of this document. Whilst there is no doubt that the asylum referred to is Wakefield, and the article is intended to convey the impression that Dickens visited the asylum personally, recording his experience, certain aspects of the report would seem to invalidate this. The fact that the article was printed three years after Dickens’ death in 1870 need not in itself invalidate claims that he visited the asylum, as this article could have been printed, as many were, posthumously.

“All the Year Round” was still, in 1873, produced as being “conducted by Charles Dickens”, and there is nothing in this particular issue to indicate that the author was other than he. Moreover, the author comments in his opening remarks that he had “seen much of the insane, visited asylums in many parts of the World…”, which Dickens was known to have done, and which “ghost” writers would have been unlikely to have done. He also accurately describes Dr. Crichton-Browne, who he refers to michievously as “Horniblow” So far, therefore, there would have been little to question. One paragraph, however, which would seem conclusively to discount Dickens’ authorship, relates to an attack by a patient on an attendant in which the latter was fatally injured.

This was an unusual case, well described in the article, which careful research shows occurred on the 22nd March 1871, almost a year after Dickens’ death. Unfortunately no mention is made in Dr. Crichton-Browne’s reports of any such visit, and there are no Visitors Records for this period. Examination of Patients’ records for this period to see if any further light can be thrown on the matter drew a blank, as no doubt the names of various patients mentioned in the article were nommes des plume.

L Ashworth.

Below is the transcript refered to by Mr Ashworth, it makes entertaining reading.

……………………………………………………………………………………..

From “ALL THE YEAR ROUND” . 13th September, 1873 page 469

(Wakefield) (conducted by Charles. Dickens)

“MY FRIEND THE MAD DOCTOR”

I am not a peculiarly nervous man and yet I confess that a certain feeling of distrust stole over me as I entered the fly to go and dine with my friend Horniblow, the medical director of a large county asylum in the North of England.

I had seen much of the insane, visited asylums in many parts of the world, and read much about the treatment of those unhappy fellow beings to whose dreadful disease too often death alone can bring an anodyne. It was not that when an insidious footman opened the hall door I expected to find myself in the centre of a gibbering and howling mob of fifteen hundred madmen, it was not even that I expected to be stabbed or strangled on my way to the dining room, but still a certain tinge of apprehension at being so near fifteen hundred people with turned brains, controlled by a mere handful of attendants, filled me, I confess, with a vague alarm, of which I felt half ashamed. There would be half a dozen locked doors between me and the mad folk, and it was not very likely that a crazy insurrection would wait my arrival to break out; it was perhaps rather the dread of the appearance of something horrible and startling; than the actual fear of a positive danger, that had roused my somewhat fervid imagination.

The reader perhaps imagines the director of fifteen hundred madmen a pale man with enormous bushy black eyebrows and whiskers, a large featured face, mouth hard as steel and eyes a terrible fixed power. He must be of herculean build and be able to either grapple for life with a madman or strike him dumb with a glance of the eye. My friend, on the contrary, was a handsome, slightly built man with very fair hair, long blond whiskers, the pleasantest of smiles, and the blandest and most conciliating manner. A man who, but for a certain look of calm good sense and acute sagacity, you would have taken, if you had met him in Regent Street, as a pet of society, a leader in the ballroom and a lion of the Row. To judge him correctly you should have seen him in the lunatic wards, firm yet kindly- in his study; or poring over the microscope; or watching by the dying bed of suffering and misery.

Except that the footman who received me in the hall looked rather more muscular and soldier-like than usual, there was really nothing to remind me how near I was to fifteen hundred madmen, who, if they had agreed on any definite line of action, could have torn us all to bits in five minutes. Once during dinner, between soup and fish, I fancied I heard a wild distant scream that sounded very like the shriek of some one being murdered, but it was not repeated, and I looked at my friend Horniblow, who was just then engaged in drawing a sort of ground plan on the body of a turbot; but he was calmly, intent on his task.

Presently, when the dinner was nearly over and our glasses of Burgundy were casting a little red danger signal across the white cloth, Horniblow after some remarks on the opera season and the last new novel, suddenly threw himself back in his chair with a fine pear which he began to peel, and said:

“Now, my dear fellow, I’m at your service; we have every sort of insanity here, and I’m ready to answer questions on any point you are interested. Imagine your-self a commissioner of lunacy, or two or three if you choose, and ask me anything you like.”

The doctor discussing the pear as he uttered these words, looked as bland and beneficient as if he had spent his life in a round of tranquil pleasure.

“Do you believe much in the power of the eye in intimidating the insane?”

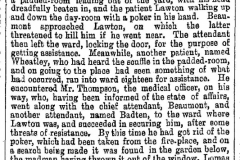

“I believe a good deal more in two strong warders,” said the doctor, with a benevolent smile. “These lunatics are always cunning, and one does not always know when they’re homicidal. I’ll give you an instance. Last March one of our attendants, a strong active man, was watching an epileptic patient, and after poking the fire, he forgot to lock up the poker as he had been especially ordered to do. He had turned his back from the man and was looking out of the window at the patients exercising in the airing-court below. All at once the homicidal impulse came with the opportunity the assassin stole softly behind him and killed him with one blow, after that beating the head to pieces. The blow was actually seen by an attendant, but too late to render assistance. The murderer afterwards, when describing his crime and praying aloud for his victim, prided himself on his accomplishment. ‘I struck him’, he said and you know I could strike, for I was a striker by trade’. The man was tried for murder three days after but being found unable to plead was sent to Broadmoor, -where criminal lunatics are confined. For a time that murder upset our whole asylum, made the patients mutinous and the attendants timid or inclined to undue severity.” (2nd March 1871 Attendant Thomas Lomas killed by patient)

“Do you effect many complete Cures?”

“About fifty per cent, and I think with improved treatment we shall be able to cure eighty per cent. Fetters, strait-waistcoats, cold shower-baths, incessant bleedings, surprise baths (where the floor of a dark room gave way under the patient’s feet and let him fall in), are all abandoned now as mistakes and barbarities and we use instead anodynes, electricity, warm baths, and generous diet. Our success is the best proof that we are nearer the mark than our ancestors were who effected fewer cures.”

“You must remark, we only admit five hundred patients out of fifteen hundred to these plays and dances, and the result is excellent. The patients learn to exercise habits of self-restraint, are pleased with the kindly questions and sympathy of the visitors and feel that they are not entirely shut out from the outer world. You would be surprised how the patients restrain themselves for fear of being prevented from coming to our weekly amusements. That effort of self-restraint is most valuable to us as a curative power.”

“What trades contribute most to your male lunatics?”

“We have nearly all trades” said the doctor, calmly sipping his wine; “but perhaps labourers, colliers and mill hands preponderate here.”

“To what do you attribute the majority of cases of insanity?”

The doctor smiled benignly, “There”, he said “you ask almost too much, but perhaps I might answer accidents at birth, congenital defects, hereditary tendency, injuries of the cranium and nervous shocks. Congestions of some organs produce insanity and drinking and vice send us many a patient. Ambition, vanity, avarice, all have their victims here. We’ll have some of them in presently, and you will hear them detail their peculiar fancies; in the mean time pass the wine which has been standing with you some time,”

I apologised for my inattention and asked the doctor if he had many spiritualists

“Not at present”, was the reply, “but many religious maniacs very much akin to those conversers with sham spirits. There was one young woman here, some time since, who believed she had committed the unpardonable sin mentioned in the New Testament. It was important to discover the special point of her delusion. Over and over again I pressed the subject. At last, one day, in a quiet mood if melancholia, she confessed that from vanity she had once shaved her eyebrows. Another patient I had, who, laying undue emphasis on the text ‘Turn ye, turn ye, why will ye die’ spent the whole day in revolving in a kind of dervish waltz, till he fairly dropped from exhaustion.”

Our conversation then turned on hypochondria and its strange delusions, which are often so ludicrous and yet so difficult to remove; and we discussed the clever strategems that had sometimes been successfully adopted to dispel these fanatic hallucinations. The doctor, as might have been foreseen, was full of illustrations of this class of insanity.

“I was very successful in one case”, he said. “A military man I attended believed that his head had been changed for that of a patient who died in the same ward. I humoured him on this point, waiting for my opportunity. Every day he used to mourn over this misfortunate and look at himself in the glass. One morning when I went to see him, I had prepared myself for a last vigorous effort to break up this delusion. The moment the door opened I looked at him full in the face, and fell back as if in astonishment. ‘What’s the matter, doctor?’, said he. ‘Matter, captain’, said I, ‘why only that you’ve got your own head back again at last’. He gave a look of surprise ran to a glass, stared at himself with astonishment and delight, and with a deep sigh of relief exclaimed, ‘God be thanked, so I have’, He was well from that moment, and never relapsed.”

“Of course,” said I, “various wholesome influences had been brought to bear on him in the asylum, and a general improvement in health had taken place before the fitting moment for you to step in arose.”

“No doubt – my experience instinctively selected the moment for striking at the delusion. By-the-bye, I’ll tell you a curious instance from the casebook of a friend of mine, who is at the Newcastle asylum. It is an extraordinary and typical instance of a thought being stereotyped in the mind by a cranial injury. In this case it was the man’s leading thought at the time the injury was received. He was an engineer employed in the construction of cannon at Sir William Armstrong’s factory. He was struck by a splinter of iron, and was for a time deprived of sensibility; when he recovered consciousness he was insane, and all his ideas turned upon huge guns. His constant delusion was that he could mow down whole armies at one discharge by means of a machine which he himself had invented, and he used to perpetually toil at turning the handle of this imaginary machine till he was ready to drop from exhaustion.”

“I have heard cases,” I said “where blows on the head have benefited the brain and produced extraordinary changes for the better.”

“Just so,” said the doctor, rubbing his own head approvingly. “Mabillon was almost an idiot till, at the age of twenty-six, he fell down a stone staircase, fractured his skull, and was trepanned. From that moment he became a genius. Doctor Prichard mentions a case of three brothers who were all nearly idiots. One of them was injured on the head, and from that time he brightened up, and is now a successful barrister. Wallenstein, too, they said, was a mere fool till he fell out of a window, and awoke with enlarged capabilities. I had a patient here a short time ago who was the victim of many delusions. He was paying off the national debt, going into partnership with Baron Rothschild, and forming a lodge of female freemasons. One day an epileptic patient, irritated at being perpetually asked to buy imaginary shares, gave him a tremendous blow on the bridge of the nose. From that time he improved rapidly, and told me that the blow had had a sobering effect, and had quite knocked the nonsense out of him.”

“You had better start a sparring school at once,” I suggested.

“There is no doubt,” said the doctor smiling, “that this was the secret of that cruel old remedy for madness – the circulating swing, mentioned favourably by physicians of the last century. This horrible swing was a small box fixed upon a pivot, and worked by a windlass. The ‘inflexible’ maniac, or the maniac expecting a paroxysm, was firmly strapped in a sitting or recumbent posture. The box was then whirled round at the average velocity of a hundred revolutions a minute, and its beneficial effect was supposed to be heightened by reversing the motion every six or eight minutes, and by stopping it occasionally with a sudden jerk. The results of this swing (Which occasionally brought on concussion of the brain) were profound and protracted sleep, intenser perspiration, mental exhaustion, and a not unnatural horror of any recurrence to the same remedy, which left a moral impression that acted as a permanent restraint.

“The cases of suspended consciousness after brain injury are also well worthy attention,” continued the doctor, after a pause. “A man who awakes out of sleep is conscious of a lapse of time, and can generally even guess its duration but the man struck on the brain is often unconscious of any lapse I knew a man who was in the asylum in ‘seventy-one, who had been struck in the street and was afterwards delirious and maniacal for ten weeks. When he became more tranquil, they brought him here in a strait-waistcoat. He soon recovered, but when he became conscious he had clean forgotten the fourteen days’ trance, and the ten weeks delirium and mania. I’ll give you another example: at the battle of the Nile an English captain was struck on the head by a shot and became unconscious. He was taken home with the wounded, and remained in Greenwich Hospital fifteen months deprived of sense and speech. At the end of that period an operation was performed and the brain relieved from the pressure, He instantly rose from his bed, and continued the orders to the sailors which had been so abruptly interrupted fifteen months before. Dr. Abercrombie gives an analogous case. A lady was struck with apoplexy while sitting at the whist table. It was Thursday evening when she fell, and she lay in a stupor all Friday and Saturday. On Sunday she suddenly recovered her consciousness; and her first words were, “What are trumps?” The clockwork had stopped at the point, and now the pendulum again commenced to swing.”

“Very interesting,” I said; “but how much we have to learn before we know that clockwork thoroughly. Microscopic differences seem to be the boundaries between health and disease, great intellects and small; to the microscope then we must trust, and to the study of years of examples. We certainly owe much to Gall and the phrenologists for drawing attention to the study of the brain, and for trying, however imperfectly, to localise the faculties. It was a tremendous step forward from the dreamland of the metaphysicians.”

“It was, indeed. Of’ all Gall’s researches, those, I think, on language were the most imperfect, because he tried to localise too much. Doctor Browne of the Chrichton Royal Institution, has written a most curious and interesting essay on aphasia, or loss of speech in cerebral diseases, which bears on this subject; the doctor shows that it is certain some part of the brain must be injured before this loss arises, but then there are many sorts of deprivation. Doctor Browne gives some most extraordinary instances of this but I’m tiring you out.”

“Tiring! What did I come for but to consult the oracle?”

“The oracle is obliged to you for the compliment; and, moreover, as you seem interested upon this curious question of brain diseases affecting the organ of language, the oracle will now give you a few notes from various sources on this very subtle subject. Without discussing such technical subjects as to whether local or general disease of the brain leads to partial or total deprivation of the power of language, I will read to you, my patient listener, a few of the most remarkable cases of such deprivation, which is called by us oracles aphasia. You have, of course, observed how a particular word will sometimes refuse to come at the bidding of the writer cr speaker. Such instances are specimens of temporary aphasia.

The clockwork, for a moment, refuses to act. The memory, for a moment, seems paralysed, or in a stupor. Doctor Jackson, of Philadelphia, relates a case of cerebral irritation, which did not affect either intelligence or memory; but the patient could only repeat one grotesque form of words, which were always ‘Didoes doe the doe.’ He was bled and soon recovered. Mezzofanti, the master of sevent two languages was entirely deprived of them all by a brief attack of fever. The moment the attack subsided, the languages all flew back like bees to the hive. In these cases, when the power or will to use intelligible lanage seems gone, there is sometimes substituted a jargon (as we call it in asylums) peculiar to the patient, and with a mark& character of its own,”

I expressed my great interest at this.

“Well, I allow it is worthy of your astonishment, and would only be observed by Oracle who have a wide experience of all forms of insanity. A patient at the West Riding Asylum, in 1868, uttered words all framed on this model. The following were words taken down from her lips, and all of them had a vague resemblance to Greek: ‘Kallulios, tallulios, kaskos, tellulios, karoka, keka, tarrorei, kareka, sallullios ‘

“She would utter this jargon for hours together, and ask or answer questions in this self-manufactured language, and seem surprised that no one understood it. Not unlike this strange talk was the ‘unknown tongue’ spoken by the Irvingites when in violent state, of religious excitement, about forty years ago. A Scotch pamphlet of the time gives the following as divinely inspired utterances to which the less gifted listened with awe and amazement: “Hippo, garosta, hippo, booros, schoote, Foorime, corin, hoopo, Jamo, hoostin, hoorastin, hiparous, Hispanos, Bantos, Boorin, 0 Pinitos, Elalastina, Halimungitos, Dantitu.'”

“Now, unless these could be shown to be words of real languages and language unknowns to the speaker, they merely show a power in certain minds when excited (and madness is only a super-excitement) of inventing words which only the insane seem to have the power of remembering and using again. At the very same period a medical man took down the following jargon from the lips of a patient in the Montrose Asylum who had never heard of Irvingism: ‘Ellueam, vuruen, errexuen, vaulem, betheram, ullem, dathureem, been tuurem, elleruem, vara, ellevera, exulle, dathellia, vipers, civeu, uremia, vas, cillera, exeram, datherveam, liaulveiliucuem, villera, repthallon, erripthulton, bilirea, ebillerea, lubluron, eluvuron etc.”

“The natives of the Cevennes used to prophesy and speak in unknown tongues, no doubt the result of what would, in the Middle Ages, have been called ‘demoniacal possession’ out really the result of the above named causes. In some cases lunatics will talk in rhythm; and Doctor W. A. F. Browne gives a remarkable instance of one patient who, for four days and nights, spoke no words but such as ended in ‘ation’ a termination which the man added to every word he uttered. His pronunciation was correct, and the term, as far as they could be interpreted, bore some reference to the question asked him, as, for instance, ‘gratification, robustation, jollification,’ which meant that he was pleased to say he was healthy and happy This iteration gradually ceased and the man eventually died of general paralysis.

In some cases of idiom the patient can only utter monosyllables, in others they utter only oaths or roar like wild beasts; in one case the loquacity I remember was so intense that the words were all run into one long sentence. A maniac in the Salpetriere used to speak clearly and significantly, but with frightful feverish rapidity, especially when irritated. Mixed with threats of vengeance and imprecations, she used to tell those she abused, parenthetically, that she aid not mean What she said, that she loved them, and felt grateful to them for their kindness and forbearance, but that, though anxious to please them by being silent, she was constrained by an irresistable agency to speak.”

“This reminds me”, said I, the most patient of listeners, “of Lord Dudley Ward’s inability to prevent talking aloud, and uttering his opinions (not always peculiarly favourable) of persons present.”

“Exactly; his brain has been prematurely developed; he had probably incipient disease of the frontal lobes, and he eventually died insane There is a celebrated

French case, where the patient could only articulate one word “cousin” and yet could play well at draughts and dominoes. But, come, you have had enough of these medical stumbling-

blocks.” Here the doctor rang the bell and a footman appeared. “Are they assembled, John?” “Just going in, sir.”

“Now”, said the doctor, we will reduce theory to practice. This is the night of one of our weekly entertainments and I’ll make any patient you like come up and tell you his history. You will see here almost every variety of monomania, many curable, and in the state of convalescence. Come with me, but you must have a glass of sherry first.”

We first discussed the sherry, and the doctor then led me through the corridors of several wards into the ball-room, with bare floors and a gallery for the musicians. At one end was a sort of alcove; the medical attendants and the guests (including many ladies) were seated. On either side of the room, four or five deep, sat the patients, the men one side, the women on the other, quiet and contented. Here and there a melancholy madman turned away moping apart, absorbed in his own weary thoughts and apparently unconscious of what was passing. Soldier-like attendants and young nurses, trimly dressed in black, attended to the patients or chatted together. Here and there an eye turned to the doctor, but I saw no look of fear or alarm. Every one was on his best behaviour. It was evidently remembered that oddly behaved and excitable people had before now been expelled.

In the intervals of what is called, I believe, in asylum, the “Circassian round” a sort of march past of all the patients, with a four handed reel at intervals, rather a ghastly and insane kind of dance it must be confessed, but still suited to every capacity -I entered into conversation with a fussy little man with a wooden leg, who assumed the manner of one in authority. I set him down at once as a mechanic who had been a foreman and I heard afterwards that my conjecture was right. He had worked at some dockyard, and had tormented the ministers by incessantly haunting Downing St., and soliciting interviews about some mad scheme of national defence. It had become at last necessary to put him under some restraint. He seemed perfectly happy and evidently believed himself to be very useful and talked nonsense in the most rational way possible. He had a way of conveying troops underground to the seaports to prevent invasion. He knew how to do it. He had laid the matter before ministers, It could be done as easily as you raise your hand; but there were the Jesuits against it. As he changed the subject every half-sentence, it was rather difficult to follow the scheme minutely. He was all winks and smiles, and spoke so confidentially, as if it was unnecessary to more than hint at a plan so perfectly understood and so entirely practical. All at once he drew me on one side and whispered “You know where the place underneath here leads to?” I confessed I did not. “To H.E.L.L.” He said this winking with gcod-natured cunning and sanity.

“Oh, that-old fellow will talk for ever” said the doctor whom the saviour of the nation eyed with good-natured approval. “Come here and I will show you a curious ease of religious monomania.”

We walked down the long room till we came to a gloomy, big, sturdy looking man sitting in the second row.

“Phillpot” said the doctor, “come here and tell this gentleman about that affair of yours in York Cathedral the other day.” It appeared that Phillpot a week or two before, in a fit of religious enthusiasm, had stood up in York Cathedral and denounced the preacher as a “whited sepulchre.”

Phillpot made his way to the front benches and stood up before us, evidently in rather a troublesome mood.

“Well, how are you this evening, Phillpot?” inquired the doctor; “tell this gentleman how the whole thing happened.”

“Oh. I’m all right,” said the refractory patient, “but I don’t want to speak of the affair, Doctor Horniblow. Look here, I’m quite well and all I want is to get back home to my work and maintain my family. That’s what I want and so I tell you.”

The doctor looked slightly surprised at Phillpot’s refractoriness, but otherwise as bland as ever. All he did was to give the sturdy fanatic a slight push on the chest, such as a schoolmaster gives to a stupid boy who dues not know his lesson. “There go back to your place ,” he said, “we shall see to that all in good time.

As if on purpose to give me a good specimen this time he passed a little lower down the long line of seats and called out a man from the third row. “This man” he said “we have been treating with Calabar bean with great success. He will go out soon. Delusion that he is the Larl of Pomfret and King of Jerusalem.” The man, a tall sturdy mechanic stood up and came nearer to us. “Well Jenkins,” said the doctor, “better today?” “Much better, doctor; feel nearly well now.”

“You’ll soon be all right. That man we are opposite to now” said the doctor, stopping, “is a case something like what we were speaking about. He will go on talking for hours without coherence or the slightest meaning,”

The doctor spoke to the man, who at once stood up, and began in interminable harangue, the words of which were intelligible but in which there was no other cohesion.

“There, that will do, my good man, go to your seat,” said the doctor, and the patient quietly became silent and retired to his seat.

“Johnson” said the doctor, beckoning to a young alert looking man, near the end of the room “how are you?” “A stud-groom of Count Lagrange,” said the doctor to me in a low voice; “insanity produced by a kick of a horse much better, will soon go out.”

Johnson came out, answered a few questions from me about his health and told me that he was very nearly well, he hoped, and retired to his seat in a most respectful way.

“Now here”, said the doctor, locking at an anxious looking artisan in the second row “is a bad case of monomania. The man is an engine fitter and thinks he has discovered perpetual motion, a not uncommon form of insanity among clever engineers. You shall hear him. Here, Wilson, come out here and tell this gentleman about this discovery of yours. He feels a great interest in these things.”

Wilson, a stunted looking artisan, with an absorbed look, rose and stepped out at once.

He came up to me as the doctor walked on to say a kind word to other patients and plunged at once into tehnical details, with one finger of the right hand placed on the top of a finger of the left, as when we argue difficult points.

“You see, sir” he said “there is no reason in the world why this engine shouldn’t go up mountains. From the flywheel we carry a band. The ratchet pinion is locked in. So the driving band runs around.,” and so on for some five minutes till I was rather glad when the doctor came back, and quickly reconsigned Wilson to his seat with “The gentleman understands all about it Wilson, now; that will do.”

“This young man” said the doctor, calling one from the ranks, a young mill hand of the ordinary type, and introducing him formally to me, “you will be interested to hear, is the son if the Emperor Nicholas cf Russia. Tell him where you were born my man.”

with the utmost seriousness the man began to tell me how the Empress, his mother, came to London in 1858 and lodged at No. 6 Greenarbour Lane, hoston, where he was born.

“The worst of it is,” said the doctor, “that this young gentleman has such expensive ideas. It was all I could do yesterday to prevent him ordering two thousand rounds of beef.”

“Three thousand, doctor, and why not?”

“And five thousand legs of mutton. He thinks nothing of money.” “why should it? Ain’t I able to pay for them?”

“of course you are. There, I think you are getting on well. Go to your seat lad. You see that Gold man sitting down by the man who has the scheme for national defence?”

“Yes; he told me he was as comfortable as he could be considering.”

“Yes, he’s very quick and rational and works at his trade with us, still he nearly killed a man a month or two ago. Lunatics are very deceptive.”

Just then a little, smiling elderly woman with thin greasy black ringlets who had been waltzing vigorously wlth a fat imbecile looking girl halted near us and began to simper and curtsy.

“This lady” said the doctor, introducing me, “you will be interested to hear was cook to his Majesty George the Fourth,” The lady simpered assent.

“Tell this gentleman what was his majesty’s favourite dish?”

“Roast mice and onion sauce” simpered the ex-official and again capered off into a wild but not badly executed waltz.”

“I will now show you a case of hypochondria” said Proctor Hornibiow, “or of some form of gastric disease conjoined to monomania.”

We passed over to the woman’s side and there, next to a fat and healthy but perfectly I hopeless madwoman, sat a worn-looking, anxious mechanics wife, with a depressed and disconsolate expression. “Tell this gentleman about the snake that you swallowed” said the doctor in a kind and sympathising way.

The poor woman rose respectfully and told me how three months before in eating a bit of raw turnip, she felt that she had swallowed the egg of some animal. Since then she had constant pains and latterly she could feel a snake come up and eat whatever she swallowed.

“You must give me a lift here” whispered the doctor as we turned away for a moment. “We are going to show her tomorrow a small blindworm and pretend that she has vomited it. I really think it may answer.”

I turned and asked her a few questions and then told her that the doctor was very soon going to give her a very powerful medicine which he believed would either certainly kill the snake, or in some way finally relieve her.

The poor woman gave rather a cold assent to the hope and we passed on just as the terrific march round was recommencing for the last time before the strange party broke up.

“We have a great deal to learn about these mysterious diseases” were the doctor’s last words to me as I got into my fly. “But we are going on I really do think in the right direction.”

And I thought so too………

…………………………………………………………………………….

“Never Has A Man So Embodied The Spirit Of The Age”.

In speaking the above words, the British author, Peter Ackroyd, perfectly sums up everything that Charles Dickens was and is.

Charles Dickens was born in Landport, Hampshire.His father was a clerk in the navy pay office, who was well paid but often ended in financial troubles. In 1814 Dickens moved to London, and then to Chatham, where he received some education. He worked in a blacking factory, Hungerford Market, London, while his family was in Marshalsea debtor’s prison in 1824 – later this period found its way to the novel Little Dorrit (1855-57). In 1824-27 Dickens studied at Wellington House Academy, London, and at Mr. Dawson’s school in 1827. From 1827 to 1828 he was a law office clerk, and then worked as a shorthand reporter at Doctor’s Commons. He wrote for True Son (1830-32), Mirror of Parliament (1832-34) and the Morning Chronicle (1834-36). He was in the 1830s a contributor to Monthly Magazine, and The Evening Chronicle and edited Bentley’s Miscellany. In the 1840s Dickens founded Master Humphrey’s Cloak and edited the London Daily News.

These years as a journalist left Dickens with lasting affection for journalism and suspicious attitude towards unjust laws. His sharp ear for conversation helped him reveal characters through their own words. Dickens’s career as a writer of fiction started in 1833 when his short stories and essays to appeared in periodical. His SKETCHES BY BOZ and THE PICKWICK PAPERS were published in 1836; he married in the same year the daughter of his friend George Hogarth, Catherine Hogart. However, some people suspected that he was more fond of her sister, Mary, who moved into their house and died in 1837. Dickens requested that he be buried next to her when he died and wore Mary’s ring all his life. Another of Catherine’s sisters, Georgiana, moved in with the Dickenses, and the novelist fell in love with her. Dickens had with Catherine 10 children but they were separated in 1858. Dickens also had a long liaison with the actress Ellen Ternan, whom he had met by the late 1850s.

The Pickwick Papers were stories about a group of rather odd individuals and their travels to Ipswich, Rochester, Bath and elsewhere. Dickens’s novels first appeared in monthly instalments, including OLIVER TWIST (1837-39), which depicts the London underworld and hard years of the foundling Oliver Twist, NICHOLAS NICKELBY (1838-39), a tale of young Nickleby’s struggles to seek his fortune, and OLD CURIOSITY SHOP (1840-41). Among his later works are DAVID COPPERFIELD (1849-50), where Dickens used his own personal experiences of work in a factory, BLEAK HOUSE (1852-53), A TALE OF TWO CITIES (1859), set in the years of the French Revolution. GREAT EXPECTATIONS (1860-61), the story of Pip (Philip Pirrip), was among Tolstoy’s and Dostoyevsky’s favorite novels. The unfinished mystery novel THE MYSTERY OF EDWIN DROOD was published in 1870.

From the 1840s Dickens spent much time travelling and campaigning against many of the social evils of his time. In addition he gave talks and reading, wrote pamphlets, plays, and letters. In the 1850s Dickens was founding editor of Household World and its successor All the Year Round (1859-70). In 1844-45 he lived in Italy, Switzerland and Paris. He gave lecturing tours in Britain and the United States in 1858-68. From 1860 Dickens lived at Gadshill Place, near Rochester, Kent. He died at Gadshill on June 9, 1870.

Although Dickens’s career as a novelist received much attention, he produced hundreds of essays and edited and rewrote hundreds of others submitted to the various periodicals he edited. Dickens distinquished himself as an essayis in 1834 under the pseudonym Boz. ‘A Visit to Newgate’ (1836) reflects his own memories of visiting his own family in the Marshalea Prison. In ‘A Small Star in in the East’ reveals the working conditions on mills and ‘Mr. Barlow’ (1869) draws a portrait of a unsensitive tutor.

Source. http://walkawhile.tripod.com/id17.html